Should Bob Woodward have revealed the president's quotes earlier?

The ethics of journalism has some new questions.

Yesterday’s media coverage (and I assume, coverage for the foreseeable future; or until the next crisis) of Bob Woodward’s book about President Trump presents us with some ethical dilemmas in media.

One, the ethics of journalism: should Woodward have told the public what the president said privately about the severity of the coronavirus at a time when he was publicly playing it down?

Two, the ethics of sycophancy: what is the role of the people in Trump’s orbit who defend him, complicit to his actions and behaviors, and how should the media treat these sources?

First: Bob Woodward’s book, through 18 sit-down interviews with the president, revealed Trump to have known the potential deadliness of the coronavirus.

In a January 28 top secret intelligence briefing, national security adviser Robert O'Brien gave Trump a "jarring" warning about the virus, telling the President it would be the "biggest national security threat" of his presidency. Trump's head "popped up," Woodward writes.

O'Brien's deputy, Matt Pottinger, concurred, telling Trump it could be as bad as the influenza pandemic of 1918, which killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide, including 675,000 Americans. Pottinger warned Trump that asymptomatic spread was occurring in China: He had been told 50% of those infected showed no symptoms.

So Trump had intelligence. And on February 7, he told Woodward that this disease five times deadlier than the seasonal flu, only to tell the public on March 9:

Also something to consider: this February 28 New York Times story:

President Trump and members of his administration mobilized on Friday to confront the threat of the coronavirus — not just the outbreak, but the news media and the Democrats they accused of exaggerating its danger.

While stock markets tumbled, companies searched for new supply chains and health officials scrambled to prevent a spread of the virus, Mr. Trump and his aides, congressional allies and backers in the conservative media sought to blame the messenger and the political opposition in the latest polarizing moment in the nation’s capital.

On March 19: "I wanted to always play it down," Trump told Woodward. "I still like playing it down, because I don't want to create a panic."

CNN continues:

"Presidents are the executive branch. There was a duty to warn. To listen, to plan, and to take care," Woodward writes. But in the days following the January 28 briefing, Trump used high-profile appearances to minimize the threat and, Woodward writes, "to reassure the public they faced little risk."

And herein lies the journalistic equivalent: journalism has a duty to inform, so did Woodward have a dereliction of duty by not informing the public of what he knew? It’s tricky, for sure.

The Washington Post’s Margaret Sullivan interviewed Woodward about his process and why he withheld information. She reports:

First, he didn’t know what the source of Trump’s information was. It wasn’t until months later — in May — that Woodward learned it came from a high-level intelligence briefing in January that was also described in Wednesday’s reporting about the book.

In February, what Trump told Woodward seemed hard to make sense of, the author told me — back then, Woodward said, there was no panic over the virus; even toward the final days of that month, Anthony S. Fauci was publicly assuring Americans there was no need to change their daily habits.

Second, Woodward said, “the biggest problem I had, which is always a problem with Trump, is I didn’t know if it was true.”

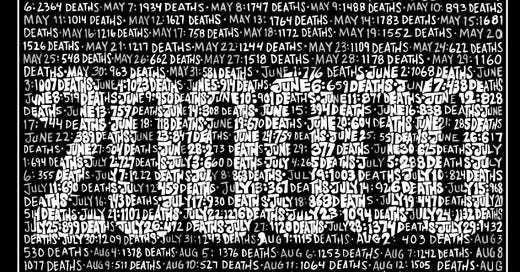

It's impossible to play counterfactual, however, there are 190k people who can't play the 'what if' game. Here’s the thing: millions of people follow the president. And it’s likely that many deaths would have been avoided had the president exhibited the seriousness of the disease and implemented protocols for states and localities on how to handle it.

I keep coming to the conclusion that Woodward should have worked with beat reporters to get this story out in late February, early March. One life saved is worth it.

Reporting could also have exerted pressure on officials to take the virus more seriously. More on this in a moment.

And of course, the president has now weighed in:

Woodward also says he's writing the second draft of history. This makes little sense, as someone currently living in the moment. We won't know the full picture for years/decades (if ever). Again, 190k people can't read this second draft.

Time’s cover story this week (which also happens to be only the second time the iconic red border goes black; the first time? After 9/11) looks at how we got here, but also subtly nods towards the idea that history, not the present, judges the president’s actions:

Although America’s problems were widespread, they start at the top. A complete catalog of President Donald Trump’s failures to address the pandemic will be fodder for history books.

What we do know: 190,000 people and counting are dead, millions of lives upended because of the disease.

In a different CNN report about the book:

William Haseltine, one of America's most respected health care professionals, who is now chairman and president of ACCESS Health International, a global health nonprofit, laid a devastating charge about the cost of Trump's negligence.

"How many people could have been saved out of the 190,000 who have died? My guess is 180,000 of those," he told Blitzer. "We have killed 180,000 of our fellow Americans because we have not been honest with the truth. We have not planned, and even today we're ignoring the threat that lies ahead."

But there’s also an ethical dilemma within the Trump administration. Officials find themselves continually defending the actions and behaviors of a president who continually shows he’s not fit for the job.

Take the press secretary, who infamously told reporters on her first day of taking over from her predecessor that she would not lie to them (which, naturally, no one believed, but also kind of shows you how Trump press secretaries view their role). This was her yesterday:

And while the president changes advisors and administration officials more often than I change my toddler’s diapers, it should be noted that many of them talk anonymously after they leave the administration to explain to the public just how disastrous Trump is. See: The Atlantic.

I’ll leave the deeper dive into the ethics and morality of Trump’s enablers here, but it should be noted that the media, in “protecting” these anonymous sources ultimately do more harm to the institution of Journalism, providing pathways towards the erosion of trust in the media.

One last bit of interestingness: this was the front page of the New York Times the day after former FBI Director James Comey wrote a letter to Congress saying FBI agents would “review” a trove of Hillary Clinton’s emails found on Anthony Weiner’s computer; three above-the-fold stories, which then led coverage for what seemed to be an eternity while derailing Clinton’s presidential campaign.

And this is the front page today, the day after we find out that the president of the United States knew the potential deadliness of the coronavirus but chose to lie and downplay the disease. One story.

Thank you for allowing me into your inbox, today and every day. If you have tips or thoughts on the newsletter, drop me a line. Or you can follow me on Twitter. If you liked this edition, please consider sharing across your social networks. Thanks!

Randy Newman, “Mr. President (Have Pity on the Working Man)”

Some interesting links:

For publishers looking for a media strategy

The Atlantic gained 20,000 subscribers after Trump dismissed it as a 'dying' magazine (CNN)

‘We’ve really reset our floor’: How The Atlantic gained 300,000 new subscribers in the past 12 months (Digiday)

For people interested in multimedia displays of reporting:

How a massive bomb came together in Beirut’s port (NYT)

For whistleblowers:

Senior DHS official alleges in whistleblower complaint that he was told to stop providing intelligence analysis on threat of Russian interference (WaPo)

For TV buyers:

ViacomCBS Chief: Upfront Ad Market 'Very Far Along' (MediaPost)

For publishers concerned about blocklists:

Google Marketing Team Admits Keyword Blocking of ‘Coronavirus’ Was Too Broad (Adweek)

For the revolving door: