How do you know what you're reading is accurate?

A quick look at Gell-Mann Amnesia.

You ever come across an article about a subject you know very well, and think: hmm, this is just...wrong? Everything from the premise of the article to some basic facts are off, and you just get mad? Like, irrationally mad? To the point where you fire off emails to friends and colleagues about how wrong this story is; take to Twitter to write a point-by-point thread of the inaccuracies of the article; maybe even write a blog post, newsletter, or a letter to the editor of how dangerous publishing inaccurate information is?

And then return to the newspaper and continue reading other articles about other industries and topics, and not even hesitate in accepting those articles as fact-based truth?

(Image via Shutterstock)

This, my friends, is called Gell-Mann Amnesia, coined by Michael Crichton, he of Jurassic Park, The Andromeda Strain and countless other science-fiction books, in 2002 at a speech in La Jolla:

Media carries with it a credibility that is totally undeserved. You have all experienced this, in what I call the Murray Gell-Mann Amnesia effect. (I refer to it by this name because I once discussed it with Murray Gell-Mann, and by dropping a famous name I imply greater importance to myself, and to the effect, than it would otherwise have.)

Briefly stated, the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect is as follows. You open the newspaper to an article on some subject you know well. In Murray's case, physics. In mine, show business. You read the article and see the journalist has absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues. Often, the article is so wrong it actually presents the story backward -- reversing cause and effect. I call these the "wet streets cause rain" stories. Paper's full of them.

In any case, you read with exasperation or amusement the multiple errors in a story, and then turn the page to national or international affairs, and read as if the rest of the newspaper was somehow more accurate about Palestine than the baloney you just read. You turn the page, and forget what you know.

I’m going to use examples from the New York Times because we as a society all agreed, at some point a long time ago, that it was the preeminent news source. If we are to hold this outlet as an example of exemplary journalism, of which it is, then we should also be able to hold it accountable when we see patterns that are problematic.

It’s one thing to debate the merits of an issue; it’s another to understand when the foundation of facts is presented in the wrong way.

Take, for example, this critique on a recent piece in the New York Times about net neutrality (which argued that “net neutrality is one of America’s longest and now most pointless fights over technology”) from one of the people who literally wrote the rules at the FCC.

Or how about wading into the paper’s recent story on Slate Star Codex, which has riled up Silicon Valley insiders. But what happens when the former editor of Wired weighs in to both defend the author of that article AND call the piece “a mess, both in process and content”?

There has been a conversation from the tech sector that the reason reporters get tech stories wrong is because those reporters have never worked in tech. That is reductive logic that tries to cast blame on the reporter. It’s misguided, at best. For example, would that mean that the only people who could credibly cover the president of the United States is ... a former president?

Yes, having experience in an industry helps cover that industry—it’s not surprising that some of the clearest writing about, say, the legal system comes from former lawyers. But it is near impossible to have an industry-level expertise in writing for a general outlet. It’s also why sourcing is vital.

We’ve talked about sourcing and framing a lot in this here newsletter, and the thread below does a great job in showing how news organizations do readers a disservice by not thinking through who gets quoted in certain stories.

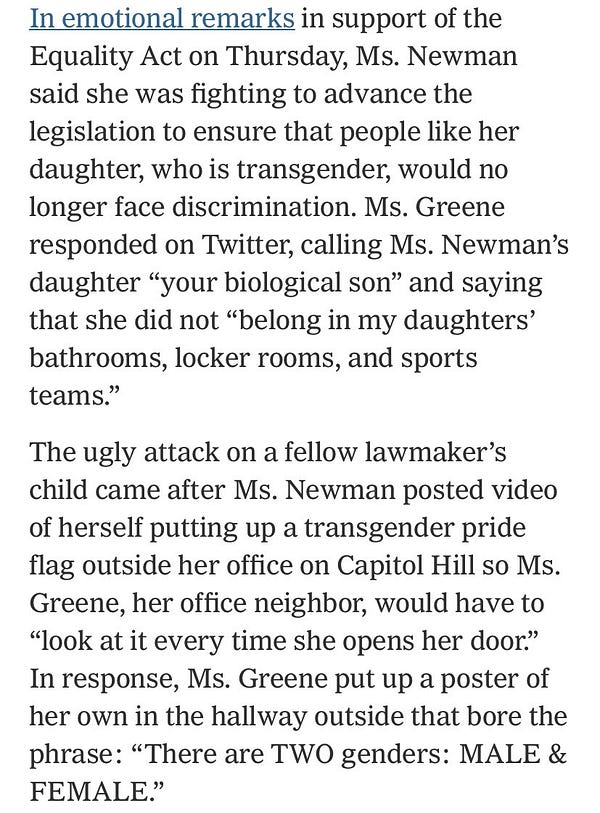

Last week, the House of Representatives passed the Equality Act, which prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity across a wide variety of society—from employment to housing to public education to federal funding and even the jury system. This thread lays out how news organizations, from the NYT to CNN, failed to give important context while also using troublesome sourcing.

And then we get to media reporting. I have my own struggles reading media coverage. Heck, this newsletter operates on the principle that media reporting often misses the mark, focusing on the wrong things.

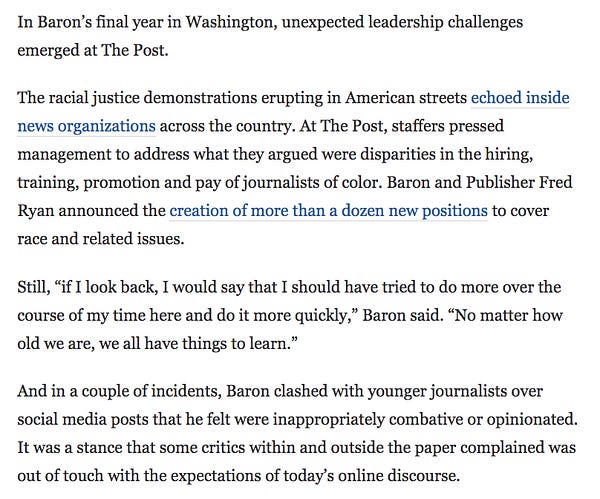

Take Marty Baron, the Washington Post’s as-of-today former editor, and his publicity victory lap. The NYT, CNN, and the Washington Post itself, among others, have put Baron on a pedestal this week.

This thread rightly highlights how while Baron and WaPo owner Jeff Bezos are important to the shape of the paper, it has taken a village. Sure, the richest guy on the planet provided the funds, and Baron ultimately signs off, but the frame of these stories — especially as “Two white guys saving journalism” — comes across as misguided.

And a former reporter who worked for Baron tried to correct some things

Speaking of missing the mark, a professor of information studies at UCLA, raised some hackles by exhibiting a poor understanding of the media business and journalism and writing a very long, but very wrong, thread on the ills of Substacks.

The thread reminds me of conversations I had with Very Serious Journalists in the early Aughts, as they railed against blogging.

The point to all of this: media literacy is non-existent in our pedagogy; we are not taught how to read media critically. So when we come across an article on a topic we know about and we know to be wrong, we choose to not put those critical thinking skills to the test across other articles in the same newspaper or outlet.

Of course, journalists and news organizations are fallible, like everyone else. And since we do our work in public, it’s easy to take us to the shed when we get basic facts wrong. And often, there is a disconnect between the reporter’s knowledge base and the editor’s. The reporter talked to a whole bunch of people; the editor may only know about the subject from their reporter’s coverage. I’ve seen this, often.

(But don’t mistake me: editors are necessary and good and are often the only reason more reporters don’t get in trouble.)

And a lot of this boils down to trust. Do we trust our knowledge set? Do we trust reporting? Do we trust the sources that serve to give readers the inside point of view?

Think about this scenario: you are writing a story on family issues. Who do you highlight as an expert:

a couple who has been married for 55 years?

a couple who divorced after 20 years?

a professor of sociology with a Ph.D in family issues?

a family psychiatrist?

All of these are experts in one way or another. A reporter should look at a wider range of sources and expertise to help inform not only how, but what we want to explicate to readers.

And this becomes a problem when television news networks and programs put on talking heads, especially including elected officials, who consistently lie. How are we to take political programs like Meet The Press or Face the Nation when they continue to put people like Senator Ron Johnson on air, and give him ample space to tell millions of viewers that Donald Trump won the election?

Perhaps we are not suffering from Gell-Mann Amnesia, and instead are living in Gaslight Nation.

Thank you for allowing me in your inbox, today and every day. If you have tips, or thoughts on the newsletter, drop me a line. Or you can follow me on Twitter. Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you tomorrow!

Phish, “Piper/Guy Forget”

Some interesting links:

For reporters going to Medium to tell their story:

NYTimes Peru N-Word, Part One: Introduction (Donald McNeil’s Medium)

For bad things happening to bad platforms:

Far-Right Platform Gab Has Been Hacked—Including Private Data (Wired)

For a look at yet another streaming plus network:

Forget ‘Succession.’ You Can Watch ‘90 Day Fiancé’ for 100 Hours Straight. (NYT)

For thinking about media models:

A New Media Structure: The Ownership Economy (Dark Star)

For new platform products for creators:

Instagram launches ‘Live Rooms’ for live broadcasts with up to four creators (TechCrunch)

For smart looks at the Golden Globes:

Streaming services do well (Axios)

The morning after: Global warning (The Ankler)

It's no secret: we're afflicted by bad reporting because publishers and broadcasters are cheap. Reliable journalism (if you need a definition, see "The Art and Craft of Feature Writing: Based on The Wall Street Journal Guide") costs money, lots of it, and owners don't want to pay for it.

The largest newspapers are still doing a decent job of reporting, but the rest merely reprint AP stories, news releases, and police bulletins. And local TV news programs fill much of the hour reporting not newsworthy events, but user-generated video of those events, and Tweets about the video. Yikes.

Our present situation is due to the disappearance of monolithic broadcast audiences for TV, and of the classifieds from newspapers. Only large injections of cash into publishing and broadcasting businesses—and the emergence of audiences willing to pay for truth and understanding—can restore reliable journalism. Journalists alone can't do it.